Instruments

Voices of history, restored and heard again

RESTORATION AND CRAFTSMANSHIP

The Violins of Hope project is rooted in three generations of violin making and restoration. Instruments are repaired using traditional methods that preserve their character while ensuring they can be played safely.

This careful work reflects a commitment to honoring each instrument’s history while allowing the violins to continue to speak and extend their musical lives.

The Violin

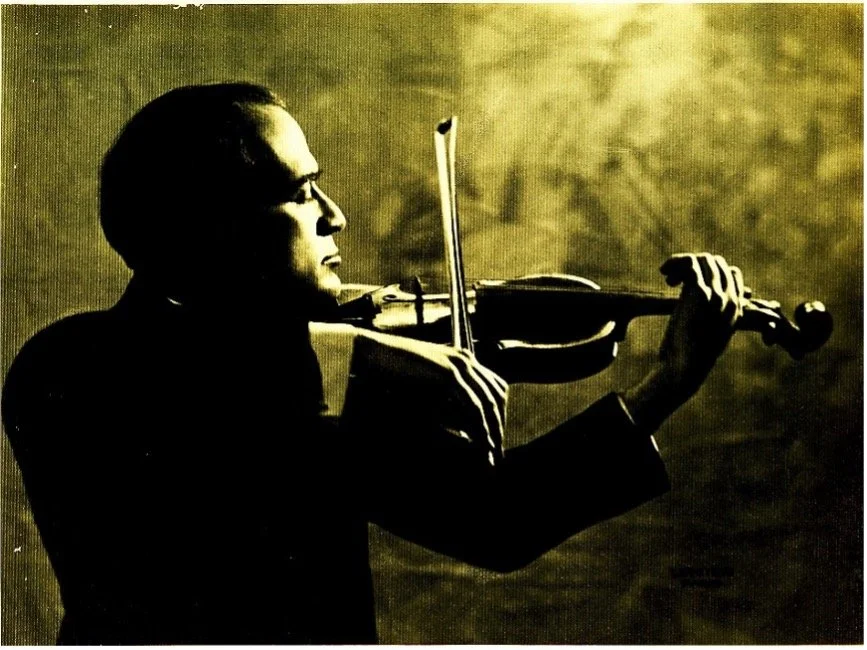

“The violin is talking. The violin is singing. And if you have a good way to listen, you can listen to all the stories.”

Amnon Weinstein

The violin is the instrument most connected to the Jewish people. It was affordable and easy to run with as Jews were hunted by the Nazis. It has served as a celebratory symbol of life. And in times of sadness, a source of hope.

During the Holocaust, Jewish musicians played the violin to bring hope to their communities. Musicians relied on their instrument to help feed their families.

And some in the concentration camps were forced by the Nazis to play music and have their lives spared while they watched their friends and loved ones walk to their deaths.

The soulful voice of the violin provided moments of escape from the horror. They couldn’t pray in the camps. The violins prayed for them.

Every instrument has a soul, or Neshama. The voices of the musicians are heard when these violins are played, which is why the instruments were repaired and not left simply to be on museum display.

THE INSTRUMENTS AND THEIR STORIES

Every instrument in the Violins of Hope collection carries a unique story. Some histories are well documented, while others are only partially known.

Together, they represent the lives of musicians, families and communities disrupted by antisemitism and violence.

During the Iowa residency, a curated selection of instruments will be featured. Each instrument is restored with care and respect so it can be played and heard or seen again. Some instruments carry Stars of David or symbolic decoration and reflect Jewish cultural identity.

“It is a true honor, and I am humbled to play Haftel’s violin and carry on his legacy. In a way, I feel chosen. As a teenager in 2026, I’m holding an artifact that survived when so many others didn’t. I feel the responsibility to play well, to work hard, and to honor the history in my hands. But more than anything, I feel inspired. Haftel shows me what it looks like to use music to bring people together, to carry hope, to preserve memory, and to remind the world that beauty can survive, even in the darkest times."

Haven, Violinist with Quad City Symphony Youth Ensemble

JHV 6 Moshe Weinstein’s Violin

This violin was a life-time friend of Moshe Weinstein, our first generation violin maker. Born in a Shtetl in East Europe, little Moishale fell in love with the sound of the violin. It happened when a klezmer troupe arrived in the shtetl to play at a rich man's wedding. While all children gathered under the table to hide and steal sweets, Moishale was hypnotized by the sound of music. After a few festive days the troupe left and so did Moishale who followed the klezmers out of town. His mother, Ester, looked for the boy to no avail.

Well, when he was found and dragged back home, he was first punished and then got a very simple violin! This was a turning point in our family history. Moishale learned to play by himself and later studied in the music academy in Vilna, where he met Golda, a pianist, and both immigrated to Palestine in 1938.

Before leaving Europe, Moshe Weinstein went to Warsaw to study with Yaacov Zimermann to repair string instruments. Since most Jews play violins, thought Moshe, they would need a violin maker in the new land. He first worked in an orchard picking oranges and a year later opened a violin shop in Tel Aviv.

Loyal to the tradition of helping out young prodigy kids making their first steps in music, he supported many Israeli talented children, among them Shlomo Mintz, Pinchas Zukerman, Yitzhak Perlman and many others.

This violin was made by Johann Gottlieb Ficker around 1800.

JHV 33 The violin from Lyon, France

Hear this violin at performances by the Quad City Symphony Orchestra and Sioux City Symphony Orchestra.

In July 1942, thousands of Jews were arrested in Paris and sent by cattle trains to concentration camps in the East, most of them to Auschwitz. On one of the packed trains was a man holding a violin. When the train stopped somewhere along the sad roads of France, the man heard voices speaking French, and a few men were working on the railways, fixing them and walking at leisure.

The man in the train cried out, "In the place where I now go, I don't need a violin. Here, take my violin so it may live!"

The man threw his violin out the narrow window. It landed on the rails and was picked up by one of the French workers. For many years, the violin had no life. No one played it. No one had any use for it. Years later, the worker passed away and his children found the abandoned violin in the attic. They soon looked to sell it to a local maker in the South of France and told him the story they heard from their father. The French violin maker heard about Violins of Hope and gave it to us, so the violin will live.

This violin was made in Germany around 1900.

VOH 109 Joyce Vanderveen and the AnnE Frank Connection

See this violin on exhibit at the Danville Station Library and Museum and hear it at the April 12 performance.

Joyce Vanderveen was a child prodigy in the arts. This Jewish Dutch girl became a violinist and a prima ballerina.

When the Nazis invaded Holland, Joyce’s mother was sent to the Westerbork transport camp, but she escaped. Joyce, her mother and sister found safety with farm families until they could be reunited with the father. Joyce kept this violin through all the turmoil.

After the war, Vanderveen danced in Europe and came to the United States at the instigation of the Kennedy family. She got a movie contract with Universal Pictures and performed in TV and movies.

In 1997, Joyce heard from a friend that her childhood picture was included in Anne Frank’s wall of magazine pictures over her bed.

JHV 23 The AUSCHWITZ VIOLIN

See this violin on exhibit at the German American Heritage Center.

This violin was originally owned by an Auschwitz concentration camp inmate and survivor who played in the camp’smen's orchestra.

Abraham Davidowitz fled Poland to Russia in 1939 and later returned to post-war Germany, where he worked for the Joint near Munich, Germany, helping displaced Jews living in DP (Displaced People) camps.

One day, a sad man approached Abraham and offered him his violin, as he had no money at all. Abraham paid $50 for the violin, hoping that his little son, Freddy, would play it when he grew up.

Many years later, Freddy heard about the Weinstein’s Violins of Hope project and donated his instrument to be restored and have a new life. This violin, now restored to perfect condition, has been played in concerts by the best musicians all over the world.

It is important to note that such instruments were very popular among Jews in Eastern Europe, as they were relatively cheap and made for amateurs. This particular violin was made in Saxony or Tirol in a German workshop around 1850. It carries a false label: J.B. Schweitzer, who was a famous maker in his day.

JHV 39 The Haftel violin

This violin belonged to Zvi Haftel, the first concert master of the Palestine Orchestra, later to become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, IPO. It is a French instrument made by a famous maker August Darte, in the town of Mirecourt around 1870.

Heinrich (Zvi) Haftel was one of about 100 musicians gathered by Bronislav Hubermann all over Europe in 1936 and brought to Palestine. Haftel was a distinguished violinist before the war and joined Hubermann after he lost his job in a German orchestra. Hubermann's vision to create an all-Jewish orchestra in Palestine saved the lives of many musicians and their families.

Haftel's violin is one of the best in the Violins of Hope collection.

The Wagner and Weichold violins

The Wagner violin is on exhibit at the German American Heritage Center. The Weichold violin will be played at performances by the Quad City Symphony Orchestra and Sioux City Symphony Orchestra.

Both fine, high-quality instruments belonged to members of the Palestine Orchestra, created in 1936 by Bronislav Hubermann, shown in the photo. They tell the story and history of the musicians who after 1948, became the IPO - Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

Most members of the IPO were first-rate musicians in European orchestras, but lost their positions when the Nazis came to power in 1933, and racial laws were enforced in Germany. When the war ended, there was a general boycott of German goods in Israel. So much so that the name "Germany" was boycotted on the radio.

In this atmosphere, musicians refused to play on German-made instruments, and many came to Moshe Weinstein and asked him to buy their violins. "If you don't buy my violin, I'll break it", said some. Others threatened to burn their instruments. Weinstein bought each and every instrument, as for him, a violin was above war and evil. Yet, he knew he would never be able to sell them.

After 50 years, those silent violins have come back to life. Those two extraordinary instruments can now be heard in concerts of Violins of Hope.

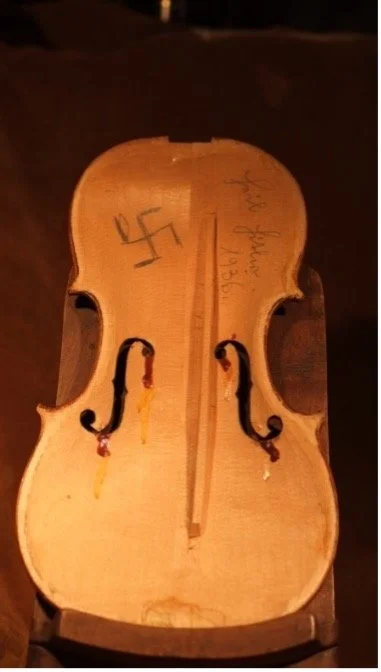

JHV 34 The Heil Hitler violin

See this violin on exhibit at the Figge Art Museum and in Tolerance Week programming in Sioux City.

This is a nondistinguished instrument, yet a puzzle. We guess that it was owned by a Jewish musician or an amateur who needed a minor repair job done in 1936. The "craftsman" opened the violin for no apparent reason and inscribed on its upper deck was Heil Hitler, 1936 and a big swastika. He closed the violin and handed it back to the owner, who played on it for years, unaware of the inscription.

A few years ago, the violin was bought by an American violin maker in Washington DC who opened the instrument and was absolutely astonished to discover what was inside. The maker's first instinct was to burn the instrument, but on second thought, he contacted the Weinsteins in Tel Aviv and donated it to the Violins of Hope project. Today, it is a part of our collection of instruments, but will not be repaired or played. Ever.

It is important to note that the majority of German violin makers were not Nazis. Many were known to support Jewish musicians who were considered to be their very talented and devoted clients and friends.

JHV 50 The Morpurgo violin: a refugee violin

Hear this violin at performances by the Quad City Symphony Orchestra and Sioux City Symphony Orchestra.

A few years ago, a 90-something-year-old lovely lady and her three daughters came to our workshop in Tel Aviv. Seniora Morpurgo and her daughters brought us the much treasured violin of Gualtiero Morpurgo, the head of the family, from Milan, Italy.

The Morpurgos are an ancient and respected Jewish family. They go back some 500 years in the north of Italy. When still a young child, Gualtiero's mother handed him a violin.

"You may not become a famous violinist, but the music will help you in desperate moments of life, and will widen your horizons. Do not give up, sooner or later it will prove me right."

That moment arrived without warning. Gualtiero's mother was forced to board the first train, wagon 06, at the Central Station in Milan. Destination: Auschwitz. Her son, Gualtiero, was sent to a forced labor camp and loyal to his mother, took the violin along and often found hope and strength while playing Bach's Partitas with frozen fingers after a long day's work in harsh conditions.

Born in Ancona, Gualtiero graduated from engineering school and worked in the shipyards of Genoa. When the war ended, he volunteered to use his engineering skills to build and set up ships for Aliya Bet, helping survivors of the war sail illegally to Palestine. For this, he was awarded in 1992 the Medal of Jerusalem by Yitzhak Rabin.

Gualtiero never stopped playing. He was 97 when he could play no more and put his life-long companion in its case. After he died in 2012 his widow and three daughters attended the Violins of Hope concert in Rome and decided that this is where it belongs – in the hands of devoted musicians in fine concert halls.

JHV 32 The Erich Weininger violin

Hear this violin at performances by ATLYS, the Quad City Symphony Orchestra and Sioux City Symphony Orchestra. While not being played, this violin will be on display at the Putnam Museum and Science Center.

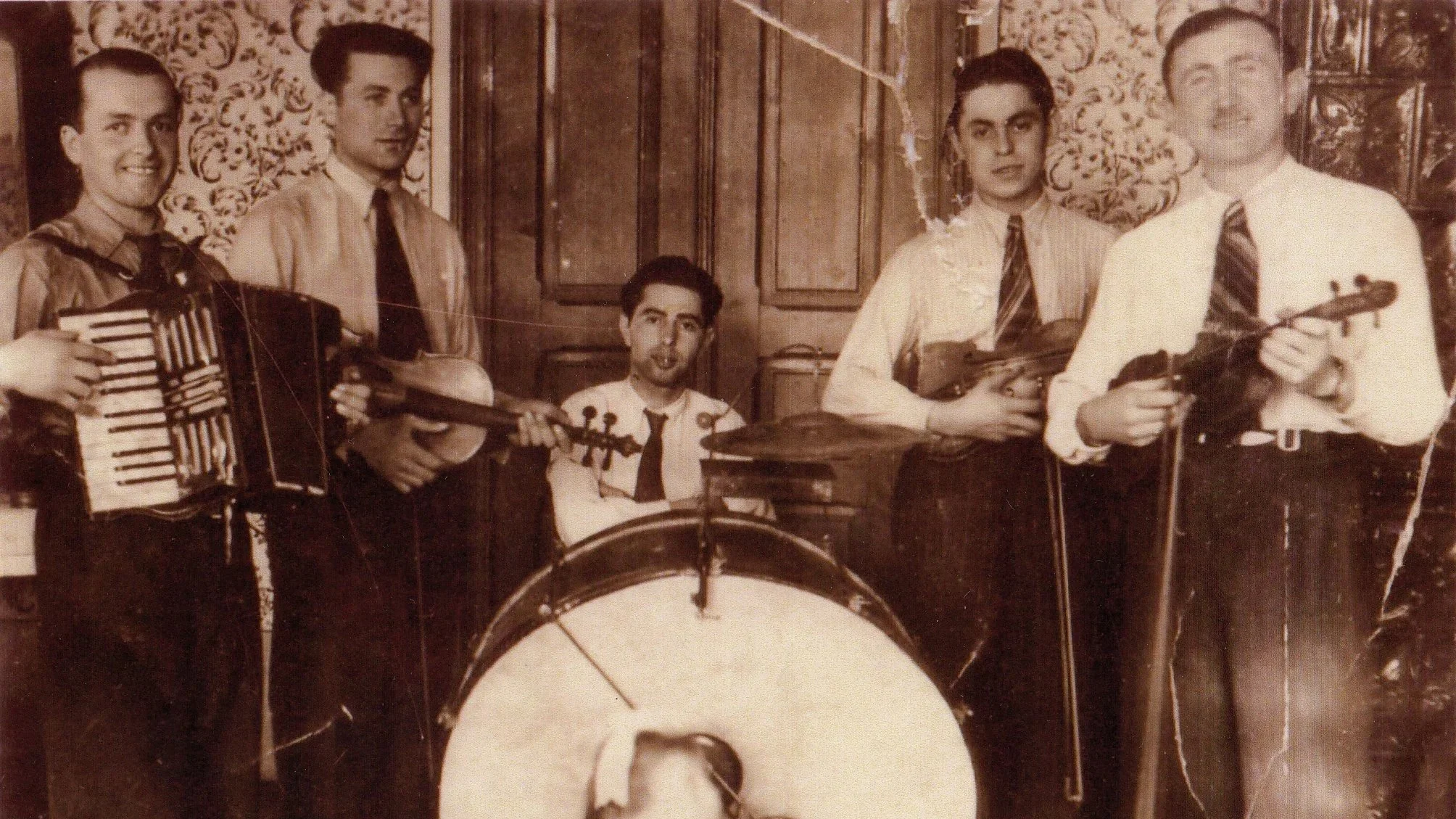

Erich Weininger was a butcher in Vienna, as well as an amateur violinist. When the Nazis marched into Austria in 1938, Erich was arrested and sent to Dachau, where he managed to bring along his violin. He was sent to Buchenwald, and though he was not allowed to play there, he still kept his violin.

In a miraculous way, Erich was released from Buchenwald with the help of the Quakers. He then returned to Vienna only to be one of the very last Jews to escape Nazi Europe. He boarded an illegal boat to Palestine, but was soon arrested by British police who did not allow Jews to come to the country. Erich, with a violin in hand, was deported to the Island of Mauritius off the coast of East Africa, where he stayed till the end of World War II.

While in Mauritius, Erich did not go idle. He started a band with other deportees, playing classical, local and even jazz music in cafes, restaurants, etc. He reached Palestine in 1945. His violin, made in the workshop of Schweitzer, Germany around 1870, was given to our project by his son, Zeev.

These violins represent the victory of the human spirit over evil and hatred. As many as six million Jews were murdered in World War II, but their memory is not forgotten. It comes back to life with every concert and every act of love and celebration of the human spirit.